|

|

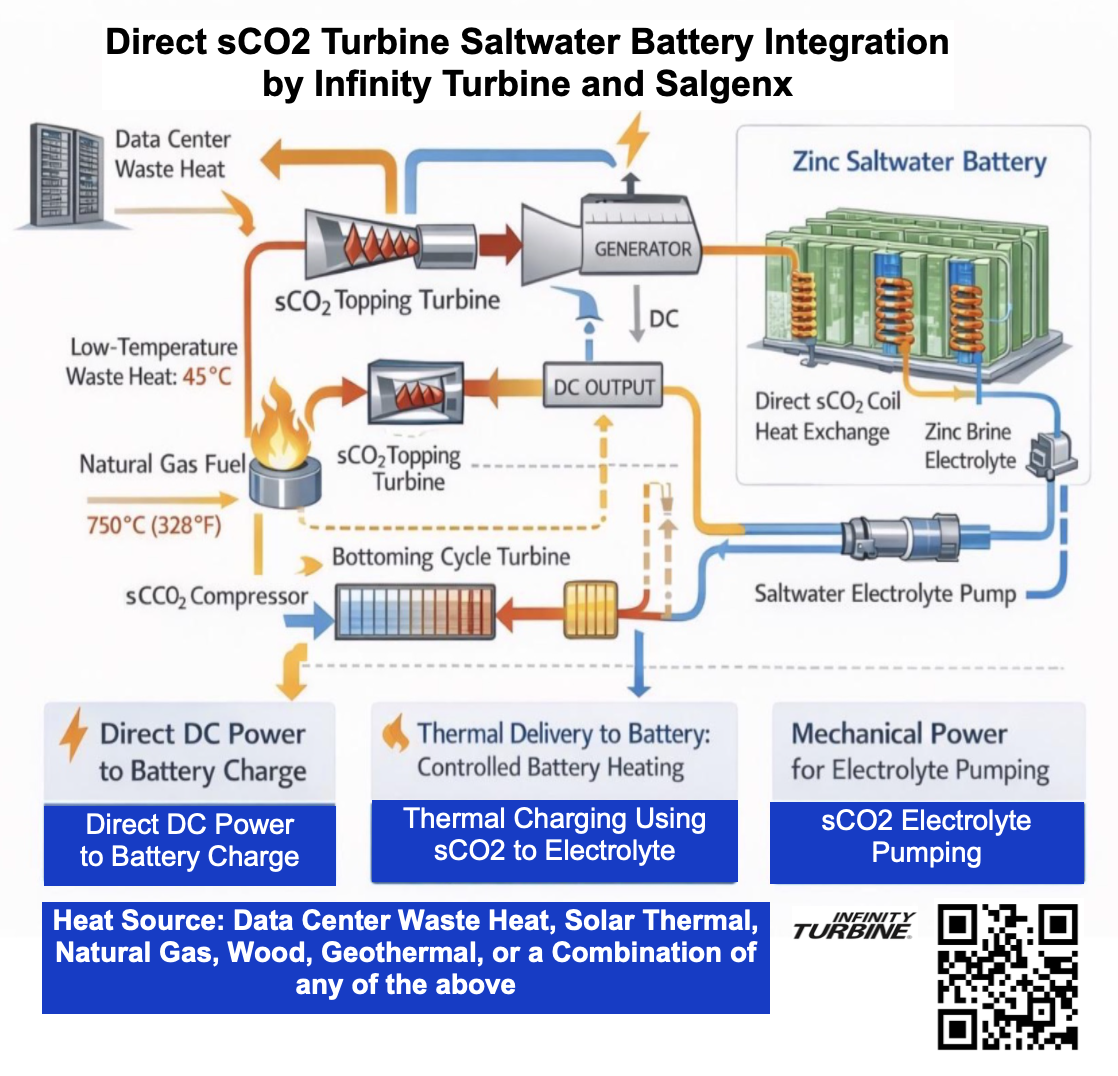

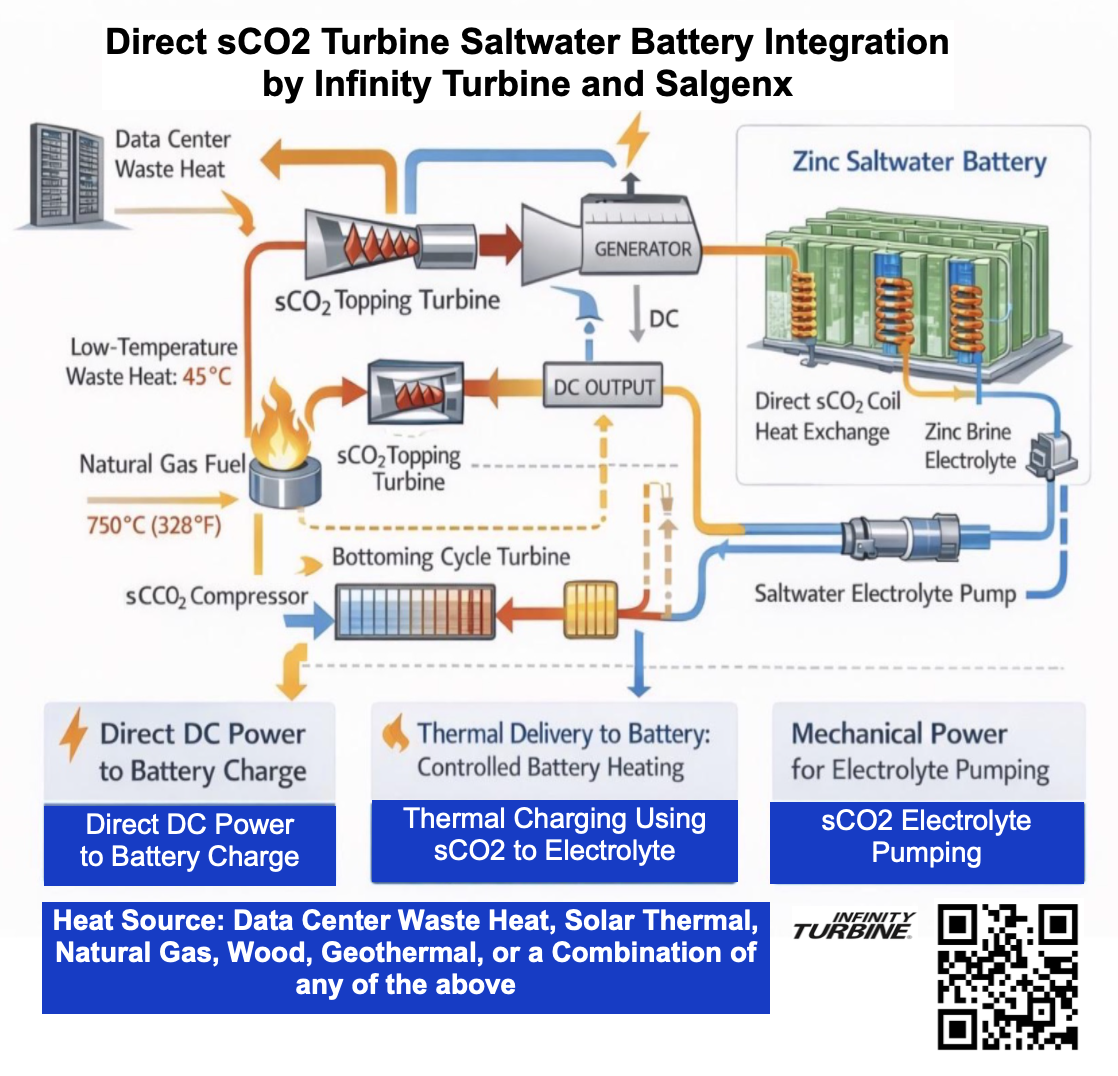

Direct sCO₂ Turbine–Saltwater Battery Integration for Low and High Temperature Energy Sources By directly coupling supercritical CO₂ turbine generators with zinc-based saltwater battery cells, electrical, thermal, and hydraulic energy streams can be unified into a single high-utilization system—scalable from low-grade data center waste heat to high-efficiency natural gas–fired combined cycles.Introduction: Converging Power Generation and Electrochemical StorageConventional power systems treat electricity generation, thermal management, and energy storage as separate subsystems connected by layers of conversion, power electronics, and auxiliary equipment. Each interface introduces losses, cost, and operational complexity.The proposed architecture collapses these boundaries by integrating supercritical CO₂ (sCO₂) turbine generators directly with zinc-based saltwater battery cells. Electrical output is delivered natively to the battery DC bus, turbine exhaust heat is used for controlled battery thermal management, and turbine shaft work assists electrolyte pumping. The result is a tightly coupled electro-thermo-mechanical system optimized for total energy utilization rather than peak standalone efficiency.Two operating regimes are considered:1. Low-temperature operation (45 °C turbine inlet) using data center waste heat.2. High-temperature operation (750 °C turbine inlet) using natural gas or other high-grade heat, with an integrated bottoming cycle.System Overview: Direct sCO₂ to Zinc Saltwater BatteryThe battery chemistry consists of zinc, salt, and water electrolytes, typically benefiting from:improved ionic conductivity at elevated temperature,reduced electrolyte viscosity,stable operation within a controlled thermal window.The sCO₂ turbine block provides three simultaneous functions:DC electrical output for direct battery charging,thermal delivery to the battery via heat-exchanger coils integrated into modules,mechanical or hydraulic power for electrolyte circulation.This configuration minimizes parasitic electrical loads and enables an exergy cascade from high-value work to low-grade thermal conditioning.Scenario 1: Low-Temperature Operation at 45 °C Turbine InletThermodynamic CharacteristicsAt a turbine inlet temperature of approximately 45 °C, the sCO₂ loop operates near the lower boundary of useful Brayton-cycle behavior. Electrical efficiency is modest, but the system remains valuable because:Compression work is minimized near the critical region.Even small pressure ratios can produce usable shaft power.Thermal energy is not wasted, but deliberately routed into battery conditioning.System Role and AdvantagesIn this regime, the turbine functions primarily as:a pressure-driven energy recovery device, anda thermal distribution and pumping engine.Key advantages include:Monetization of data center waste heat that would otherwise be rejected.Gentle, uniform battery heating that improves zinc plating behavior and electrolyte conductivity.Reduction or elimination of resistive heaters and electrically driven pumps.Net Value PropositionWhile electrical output per unit heat is low, total system efficiency is high when electrical, thermal, and hydraulic contributions are accounted for. This mode is best understood as energy recovery and conditioning, not bulk power generation.Scenario 2: High-Temperature Operation at 750 °C with Bottoming CycleTopping sCO₂ Brayton CycleAt 750 °C turbine inlet temperature, the sCO₂ system enters a fundamentally different performance class. High turbine inlet temperature enables:large expansion ratios,high specific work,strong recuperation effectiveness.The topping cycle converts a substantial fraction of fuel energy directly into electrical power delivered to the battery DC bus.Bottoming Cycle IntegrationAfter the topping turbine, significant thermal energy remains at mid-range temperatures. A bottoming sCO₂ turbine generator captures this residual heat, increasing total electrical output and flattening the temperature glide before final heat rejection.The bottoming cycle:improves total fuel utilization,produces additional DC charging power,supplies lower-grade heat ideally matched to battery thermal needs.Expected System PerformanceWhen operated as a combined sCO₂ system:The topping cycle provides high-efficiency electrical generation.The bottoming cycle adds incremental power and controlled thermal delivery.Remaining low-grade heat is absorbed by the battery thermal envelope, reducing cooling losses.This configuration approaches the behavior of a combined-cycle plant, but with electrochemical storage replacing the steam cycle.Zinc-Based Saltwater Battery SynergiesZinc-based aqueous systems benefit uniquely from this integration:Elevated temperatures improve reaction kinetics within safe bounds.Direct thermal management reduces dendrite formation risks when properly controlled.Electrolyte pumping powered mechanically by the turbine lowers auxiliary electrical draw.DC-native charging reduces inverter and transformer losses common in grid-tied systems.The battery is no longer a passive load; it becomes an active thermal and mechanical participant in the power block.Grid-Scale and Data Center ImplicationsThis architecture is particularly well suited for:data centers seeking waste heat monetization and on-site storage,modular grid-scale installations where water use must be minimized,behind-the-meter deployments requiring islanding and black-start capability.By combining generation and storage into a single thermodynamic system, the plant behaves as a dispatchable energy module rather than a collection of loosely coupled assets.ConclusionA direct sCO₂ turbine–zinc saltwater battery system represents a shift from efficiency-at-any-cost thinking toward total energy utilization and system-level optimization.At 45 °C, the value lies in waste heat recovery, battery conditioning, and parasitic reduction.At 750 °C, the system becomes a true high-efficiency combined cycle, delivering electrical power, thermal management, and storage simultaneously.The ability to span both regimes with a common architecture is the core strategic advantage: a scalable platform that converts heat—low or high—into stored electrical energy with minimal wasted energy. |

|

Power Production Analysis 1. Per 1.0 MW of input heat (1,000 kWth), and2. Per 1.0 MMBtu of input heat (where 1.0 MMBtu/hr = 293.07 kWth; so values shown in kW are also kWh per hour).Because you did not specify detailed cycle pressures, recuperator effectiveness, compressor inlet temperature control strategy, or battery thermal limits, I am using reasonable engineering assumptions consistent with your intent:45 °C turbine inlet: very low-exergy heat source → low electrical conversion, with the primary “win” being thermal utilization + parasitic reduction.750 °C turbine inlet + bottoming sCO₂: a true combined-cycle sCO₂ package → high net electric fraction, with the remainder split between useful thermal delivery to the battery and final rejection.Assumptions used (explicit)Scenario A: 45 °C sCO₂ module (waste heat mode)Net electric to DC bus: 2% of input heatDirect mechanical/hydraulic pumping power recovered: 1%Useful thermal delivered to battery thermal management (warming electrolyte/cell jacket): 60%Remaining rejected (dry cooler / ambient): 37%Scenario B: 750 °C topping sCO₂ + bottoming sCO₂ (direct-fired combined cycle)Net electric to DC bus: 52% of input heatDirect mechanical/hydraulic pumping power recovered: 2%Useful thermal delivered to battery thermal management: 25%Remaining rejected: 21%These splits sum to 100% in each case.1) Energy balance per 1 MW of input heat (1,000 kWth)| Output bucket | Scenario A: 45 °C sCO₂ | Scenario B: 750 °C + bottoming sCO₂ || -• | : | -: || Net electric to battery DC bus | 20 kWe (2%) | 520 kWe (52%) || Direct shaft/hydraulic power to electrolyte pumping | 10 kW (1%) | 20 kW (2%) || Useful thermal into battery modules (controlled heating) | 600 kWth (60%) | 250 kWth (25%) || Rejected to ambient (dry cooler) | 370 kWth (37%) | 210 kWth (21%) || Total | 1,000 kWth | 1,000 kWth |Interpretation:At 45 °C, the system is best viewed as a thermal utilization and parasitic-minimization module with a modest electrical byproduct.At 750 °C, the system is a high-efficiency combined cycle power block that also provides a large and valuable thermal management stream for the zinc electrolyte.2) Energy balance per 1.0 MMBtu of input heatUse the conversion:1.0 MMBtu/hr = 293.07 kWthSo the “per MMBtu” numbers below are simply the above values multiplied by 0.29307.| Output bucket | Scenario A: 45 °C sCO₂ (per 1 MMBtu/hr in) | Scenario B: 750 °C + bottoming sCO₂ (per 1 MMBtu/hr in) || --• | --: | : || Net electric to battery DC bus | 5.86 kWe (≈5.86 kWh per hour) | 152.40 kWe (≈152.40 kWh per hour) || Direct shaft/hydraulic power to pumping | 2.93 kW | 5.86 kW || Useful thermal into battery modules | 175.84 kWth | 73.27 kWth || Rejected to ambient (dry cooler) | 108.44 kWth | 61.54 kWth || Total | 293.07 kWth | 293.07 kWth | |

| CONTACT TEL: +1 608-238-6001 (Chicago Time Zone) Email: greg@salgenx.com | AMP | PDF | Salgenx is a division of Infinity Turbine LLC |